There’s a reason why a city’s railway station is often its most iconic landmark. Sure, its grand design or architectural innovation helps to form your first and last impression of your destination, but it’s also the stories it tells that draw you in, the people coming and going, the family reunions, the emotional farewells.

And unlike airports, many stations have a much deeper historical significance and retain a certain grandeur of a bygone era. Railtripping visited 8 of Germany’s most interesting and impressive train stations where it’s well worth to hop off, look round, and catch the next train.

Görlitz: art nouveau monument

Görlitz’s stunning art nouveau railway station, which dates back to 1917, is a relic of a different age. Germany’s easternmost station may seem a tad big for the few regional services that depart and arrive here every hour, but until the Second World War the city was an important hub in the German rail network. In the past, you could board mainline European trains to as far afield as Dresden, Paris, Wroclaw and Warsaw. This all changed though when Germany’s defeat in the war saw its eastern border moved to the Oder and Neisse rivers, and the station more or less lost its meaning.

Luckily Görlitz survived the war almost intact, and so too did its railway station. The city’s many historical buildings, including the railway station, now form a popular backdrop for films such as ‘Alone in Berlin’, ‘The Book Thief’ and ‘The Silent Revolution’.

Vienenburg: Germany’s oldest

Vienenburg railway station is located at a rail junction in the northern foothills of Germany’s Harz Mountains, and is the oldest surviving station in Germany still in operation, dating back to 1840. Only the station halls at Düsseldorf-Gerresheim (1838) and Köln-Müngersdorf (Haus Belvedere, 1839) claim to be older, but are anyways no longer in use.

The main station building at Vienenburg houses a small café, the local library, a visitor centre and the Vienenburg Railway Museum. One highlight is the steam locomotive 52 1360, which was built in 1943 at the Borsigwerke in Berlin as a so-called war locomotive, and is still operational today.

In the Kaisersaal (or ‘Imperial Hall’), connected to the station by a corridor, German Emperor William I once rested during his stay in Vienenburg in 1875. The hall is still open and can be rented for ceremonies today. The station also has direct access to the scenic Vienenburger See, with a lovely terrace on the waterside. We certainly didn’t mind waiting for the next train…

Leipzig: Europe’s largest

When you arrive at Leipzig Hauptbahnhof and walk from the platform to the main concourse, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the sheer size of this impressive art nouveau building. And no wonder: with a covered area of 83,640 m2 (or around 12 football fields), it’s the largest station in Europe. Its mighty glass roof and huge archways add to the station’s vastness and beauty, while its light sandstone facade is an impressive 298 m wide, a testament to Leipzig’s reputation for engineering, iron works and architecture.

But why Leipzig of all places? Well, it’s because the station used to be owned by both the Saxon and the Prussian railways, so they built two of everything. Two reception halls, two waiting room areas, two main stairwells — and they’re all still in use today.

The building was severely damaged by Allied bombing during World War II, especially on 7 July 1944. Hundreds of passengers and railway employees were killed when the roof over the concourse collapsed and the western entrance hall was destroyed. A memorial plaque at the western entrance remembers this tragic event today. Fortunately, East Germany’s railway operator Deutsche Reichsbahn rebuilt the western hall to its original appearance in the early 1950s.

In February 2020, Leipzig Hauptbahnhof was ranked the best railway station in Germany and the third best in Europe, surpassed only by St Pancras in London and Zürich Hauptbahnhof.

Uelzen: Hundertwasser art

With colourful pillars, glistening golden globes and trees on the roof, this could easily be the entrance to a theme park… but it’s just a railway station on the Hamburg–Hannover line, a weird and wonderful place full of artistic flair.

By the end of the 1990s, Uelzen’s old red-brick railway station was in a terrible state and lacked funds for renovation. But with the help of local activists, the Expo 2000 and Deutsche Bahn, the Viennese visual artist and architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser designed “a train station as colourful as the fantastic world of fairy tales”. Today, many claim the fairytale building is one of the most beautiful stations in the world.

Guided tours give you insight into the interplay between art, function and special details – and there’s even a colourful Hundertwasser café and restaurant inside.

Hamm Hauptbahnhof: baroque grandeur

“Hamm Hauptbahnhof, where the train will divide…” is a familiar refrain to anyone who travels regularly on the Berlin/Hannover–Cologne/Düsseldorf line. As a frequent traveler myself between Berlin and Holland, I must’ve stopped in Hamm over 100 times, but I never got off until recently. And I’m glad I did, as Hamm has one of Germany’s most impressive station buildings.

If the sign ‘Bahnhof’ and the Deutsche Bahn logo weren’t visible on the red-white façade, you could easily presume you were entering a royal palace. The current station hall was opened in 1920, and both its hall and façade feature Jugendstil elements that take you back in time. The building was partly damaged by RAF bombers in WWII, but was rebuilt and modernised after the war.

Berlin Friedrichstraße: tragic stories

In a city positively brimming with history, it’s hard to pick one train station that stands out from the rest in terms of historical significance. Many of Berlin’s stations have fascinating stories to tell, many tragic. But Friedrichstraße is perhaps the most interesting, as it played important roles in both the Third Reich and the Cold War.

‘Trains to Life – Trains to Death’ is the name of the sculpture in Georgenstraße of seven Jewish children, commemorating the 1.6 million children murdered by the Nazis as well as the 10,000 who found refuge in England just 8 months before the outbreak of WWII. In the so-called Kindertransport rescue mission, some 10,000 Jewish children were able to escape Nazi Germany and find refuge in the UK. The first train with 196 children left Berlin’s Friedrichstraße station on 30 November 1938.

During the Cold War, Friedrichstraße station became famous for being a station that was located entirely in East Berlin, yet continued to be served by S-Bahn and U-Bahn trains from West Berlin as well as long distance trains from countries west of the Iron Curtain. The station was also a major border crossing between East and West Berlin. It was reportedly used as an escape route by members of the notorious far-left militant organisation the Red Army Faction to avoid arrest in West Germany, and the station was also one of the stops on the famous Paris-Moscow Express. In the nearby Tränenpalast, or Palace of Tears, you can learn many more interesting stories.

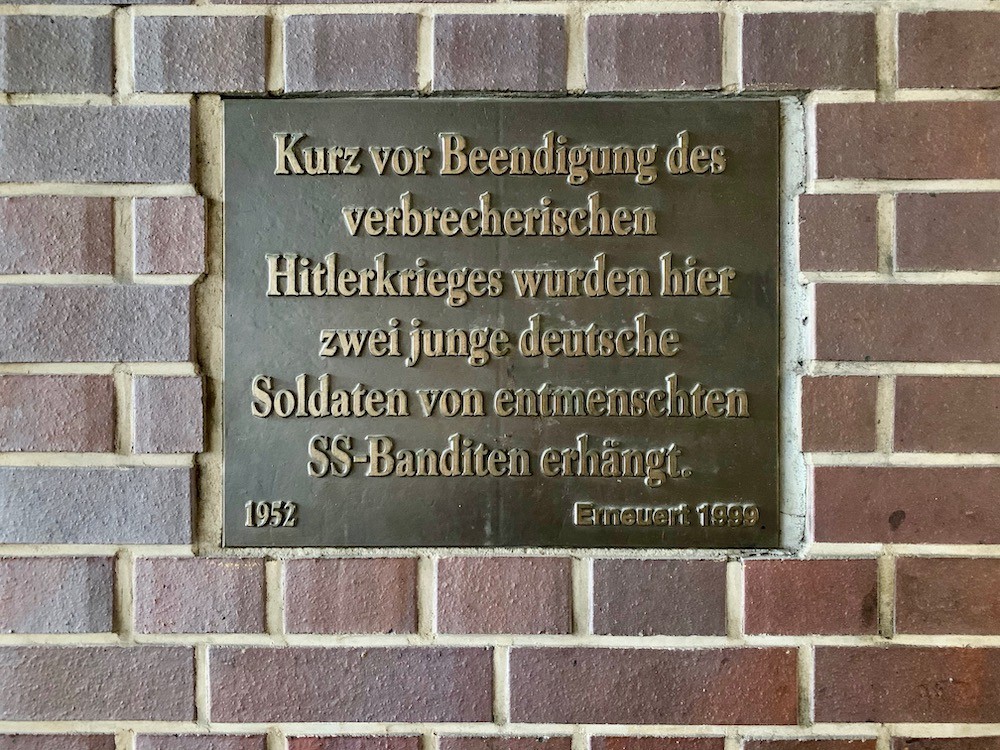

Also don’t miss the memorial plaque under the station bridge (next to McDonald’s), which commemorates two young soldiers who were hanged here during the Battle of Berlin. During the battle, any soldier that surrendered risked being killed by SS troops, who forced the population to fight until the bitter end.

Potsdam Pirschheide: former GDR icon

Getting off here, you’ll probably be the only one on the platform — a stark difference to the 1970s and 80s when up to 400 trains passed through here every day and over 100 railway employees worked. Services like Berlin-Magdeburg, Rostock-Munich and Dresden-Hamburg all stopped here, as well as holiday trains to Germany’s North Sea coast and fast local ‘Sputnik’ trains to East Berlin. Today, the GDR-style station building is still intact, and well worth a visit.

In East Germany, Potsdam Pirschheide was the city’s main station as trains from Berlin couldn’t come into the city centre. But after the fall of the wall and German reunification, they were once again able to stop in central Potsdam, which sadly meant the end of Potsdam Pirschheide, an iconic station and a rare example of GDR railway architecture.

Nuremberg: first station and first train line

Nuremberg has always been an important railway junction in Germany, and today its station with 25 tracks is one of the biggest in Europe. It was actually here that the first station in Germany was built and from here that the first rail route in Germany was inaugurated in the 1830s, from Nuremberg to Fürth. The actual building dates back to the early 1900s.

The monumental neo-baroque facade and art nouveau main hall make for an impressive site, so much so that it’s now preserved as a listed building. Check out the beautiful wall mosaics, all following the theme of travel. Also worth a visit is the nearby Nuremberg Transport Museum, which opened its doors in 1899 and is now the world’s oldest railway museum.

Some 40 iconic trains are on show in two halls, including the oldest surviving passenger coach in Germany, a replica of the country’s first steam locomotive, and a model of the ICE 4, the next generation of high-speed train.

Berlin Nordbahnhof: ghost station

This is another Berlin train station packed with history. In the 19th century, trains used to depart here for Germany’s holiday resorts on the Baltic Sea, and it soon became one of Berlin’s busiest railway stations. But after suffering heavy damage in WWII and finding itself all too close to the border between East and West Berlin, this long distance station began to lose its significance and it was eventually closed in 1952. The S-Bahn, which runs underground here, was however restored and is still running today.

Getting off at Nordbahnhof feels a bit like stepping back in time to the 1930s, with intact pre-war architecture and station signs printed in German’s old gothic script. It’s also one of 15 former ghost stations in the German capital, relics of a time when travel between east and west was tightly controlled. West Berlin was an enclave surrounded on all sides by East German territory, but three of its U-Bahn and S-Bahn lines, which had naturally been built long before the city was divided, ran through stations now located in the closed-off eastern half. To prevent its citizens from fleeing to the West by boarding these trains (today’s U6 and U8 and the north-south S-Bahn), the East German authorities forbade them from stopping, and the stations soon became deserted: hence ‘ghost’ stations.

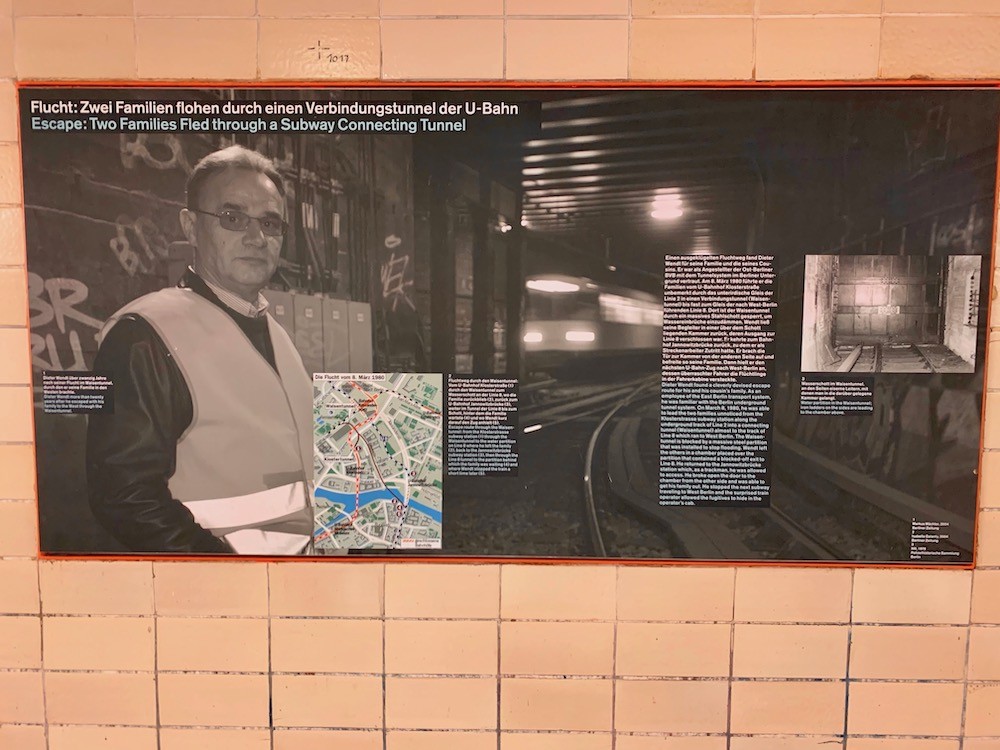

For West Berlin passengers on board, the journey into East Berlin remained a strange experience. Before entering the East, an announcement would be made over the loudspeaker “Last stop in West Berlin!”. The trains would then pass through slowly and armed guards could be seen standing on the dimly lit platforms. The absurdity of the city’s division is highlighted in a small exhibition at Nordbahnhof, which also details several successful and unsuccessful escape attempts that were made in the underground stations and tunnels.