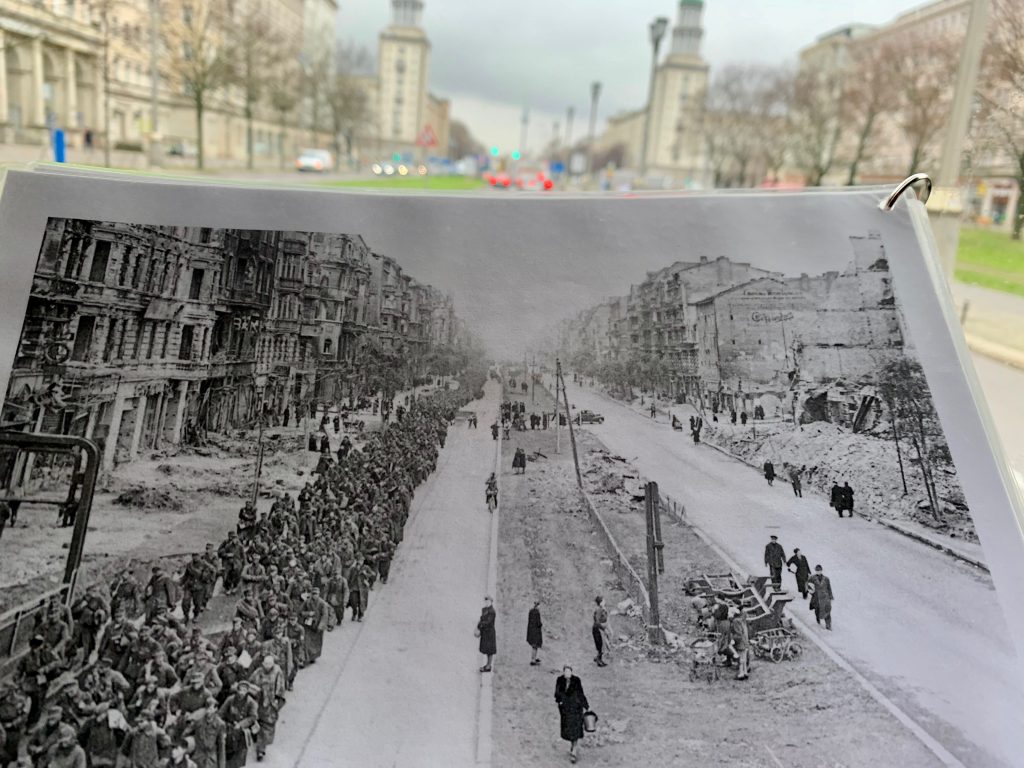

In the early hours of April 16, 1945, the 2.5 million strong Soviet Army began its assault on Berlin in the hope of defeating Nazi Germany once and for all. After 16 days of heavy fighting and at times even hand-to-hand combat, 200,000 soldiers and civilians had lost their lives and much of the city lay in ruins. Despite the devastation, several landmarks and battle scars still survive today scattered across Berlin, serving as an important reminder to the last major offensive of the Second World War in Europe.

The silent witnesses:

- Crossing the city limits: House of April 21, 1945

- Finding shelter: Anhalter Bunker

- Bullet holes & scars of war

- Brutal executions throughout the city

- The final assault: Moltke bridge

- Victory: Seizing the Reichstag

- Surrender: House at Schulenburgring

- Unconditional surrender: German-Russian Museum

- Memorials and graveyards

- What’s left of Hitler’s bunker?

- The clean up: from rubble hills to rubble women

Crossing the city limits: House of April 21, 1945

On the night of April 21, the Red Army finally crossed into Berlin in the far east of the city. The first house said to be liberated still stands today at Landsberger Allee 563 (no. 1 on the map), transformed into a memorial by the East German government, its walls painted red in tribute to the liberating Soviet Army. On its façade is written in Russian Победа на Берлин (“Victory over Berlin”) as well as the date of liberation: April 21, 1945.

As they moved towards the city centre, Soviet soldiers hoisted flags and red banners on buildings to mark their victory, including on an old church spire in the city’s Marzahn district. For the Germans, greatly outnumbered as they were in terms of soldiers, tanks and aircraft, the battle was lost before it had even begun.

Finding shelter: Anhalter Bunker

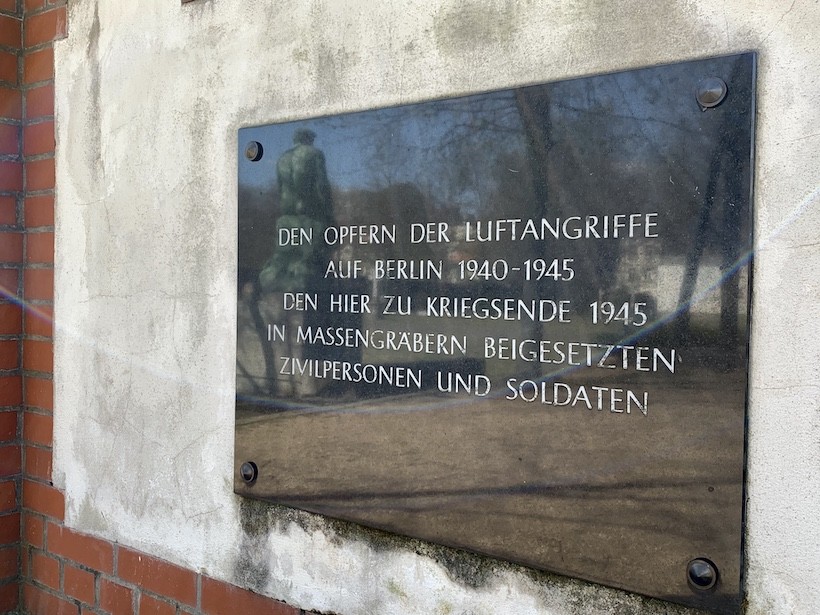

Since the start of the war, Berlin had been victim to some 360 air raids carried out by the American, British and French air forces, climaxing on February 3, 1945, when almost 1,000 US Air Force bombers laid waste to central neighbourhoods.

As the Red Army advanced, the city’s inhabitants were left constantly exposed to long-range air and mortar attacks. And with fighting on the streets and brutal, often fanatical resistance from Wehrmacht, SS and Volkssturm militias who were prepared to defend their city to the death, many civilians sought refuge in cellars, bunkers or emergency shelters set up in U-Bahn tunnels.

By 1941, five huge public shelters had been completed, providing shelter to some 65,000 people. Conditions in the shelters got steadily worse, as in the final days of the battle, the city’s water and electricity supply, as well as its sewage systems, collapsed.

The shelter at Anhalter Bahnhof (2), one of the largest still accessible today, is an enormous bunker five stories high with 100 rooms and a 3.8m reinforced concrete ceiling. Built to provide shelter for 3,500 people, the shelter was housing over 12,000 during the final days of the war in unimaginable conditions. With people packed in so tightly that they were forced to stand, ventilations systems simply couldn’t cope and temperatures rose to 60°C.

While the bunker did get hit, it didn’t suffer any serious damage and survived the war relatively unscathed. It now houses an exhibition called “Hitler – how could it happen?”, which includes a scale model of Hitler’s own bunker and a mock-up of the room where he committed suicide.

The shelters at Humboldthain (3) and Volkspark Friedrichshain (4) are also still clearly visible today.

Bullet holes & scars of war

While the Red Army made quick progress through Berlin’s suburbs, when they reached the more densely-populated inner districts they were met with fierce resistance from German soldiers and civilian militias alike. With intense house-to-house combat and heavy fighting on every street, both sides saw heavy losses. With German snipers installed in upper floors wreaking havoc at the street level, the Soviet command soon decided to destroy entire buildings with artillery, causing unspeakable damage to the city’s infrastructure.

Some buildings that survived the battle of Berlin still today bear scars from all the fighting.

Große Hamburger Straße

Reinhardtstraße

Invalids’ Cemetery

Villa Parey

Am Kupfergraben

Neues Museum

Martin Gropius Bau

Brutal executions throughout the city

To many Berliners, the morning of April 22 felt just like any other morning in wartime Berlin. The weather was overcast, shops were still open and rations were still being apportioned: 200g bread, 36g meat, 18g lard… Overnight, however, life changed immeasurably. The underground lines stopped running and the newspapers stopped printing, and soon hungry Berliners were raiding bakeries and greengrocers in search of food that was no longer being rationed.

To frighten the people, Hitler published a leaflet which proclaimed: “Anyone who proposes or even approves of measures detrimental to our power or resilience is a traitor! He is to be shot or hanged immediately!”

The atmosphere in the city was apocalyptic. From the Führerbunker, Hitler and his regime sought to prolong the war for as long as possible, even at the cost of Berlin’s inhabitants. Even children and the elderly were forced to defend the city, mostly poorly equipped. “To desert was never an option – it meant the death penalty,” said Ernst Kleine, a 19-year-old Luftwaffe member at the time.

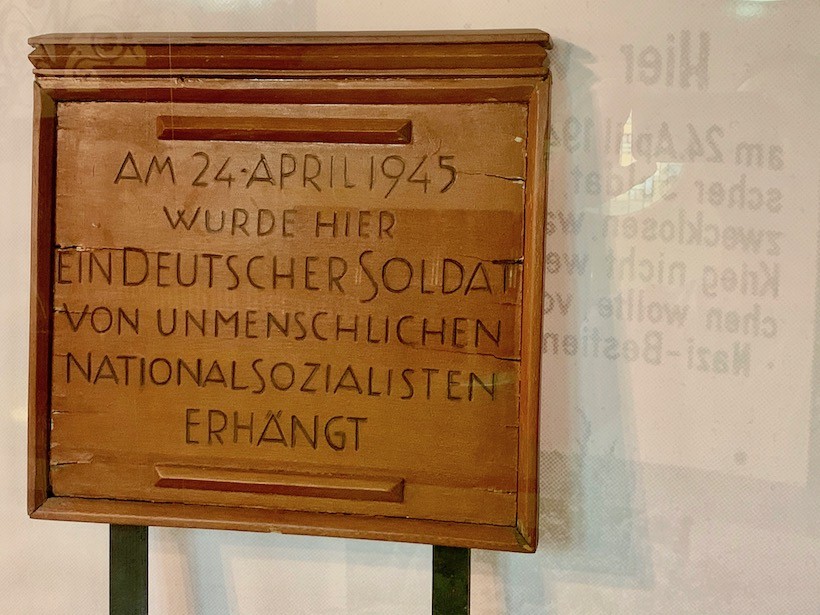

Werner Eckert, who experienced the Battle of Berlin as a child, was shocked at the cruelty shown by the Nazis to deserters. “Anyone that put a white bandage on their arm to surrender was hanged by the SS. I saw them hanging there. For one of them I even had to write a sign saying ‘I am a coward, I wanted to deliver the German Reich to communism’. There was one poor soldier at Steglitz Town Hall (11) and another near my place… It was the worst thing I experienced as a boy.”

Not only soldiers fell victim to the SS in the final days of war. Any civilian that surrendered was also executed, their bodies left at crossroads, bridges and squares to instil fear. At Zionskirchplatz (12), a man by the name of Friedrich Schwarz was hanged after raising a white flag from his window. In Schöneberg, a German soldier was hanged from a lamppost, a sign around his neck reading: “I, Sergeant Lehmann, was too cowardly to defend women and children.”

By April 25, conditions had worsened and with no electricity supply, a collapsed food supply and failing water and sewage systems, there was mass hunger and a heightened risk of epidemic.

The final assault: Moltke bridge

Hitler’s triumphant New Reich Chancellery (14) had by April 28 been reduced to rubble and the once mighty Third Reich to just a few square kilometres in central Berlin. The Red Army meanwhile was advancing ever closer to its goal: the Reichstag (15). While it hadn’t played much of a role during the Third Reich, the Soviets understood that raising their flag from the roof of the Reichstag — the seat of political power in Germany for so many years — would serve as a powerful symbol of victory.

To reach the Reichstag, however, the Soviets had to cross the Moltke Bridge (13) close to what is now the central railway station in Berlin. On April 28, they started their assault.

The Moltke Bridge had been barricaded by the Germans on both ends, wired for demolition and was heavily defended by 5,000 SS soldiers and civilian militiamen. To prevent the Soviets from advancing, the Germans attempted to blow the bridge up — but failed. In the end, enough of the bridge remained for troops and vehicles to cross over and continue towards the Reichstag, a mere 600 metres away.

Victory: Seizing the Reichstag

The battle for the Reichstag was one of the final struggles in the city’s liberation. On April 30, as fighting continued in the building’s interior, sergeants Yegorov and Kantaria climbed to the roof and raised the Soviet flag in view of the Brandenburg Gate. The now famous photo of the pair was actually taken during a staged reenactment a few days later on May 2. On that same day, soldiers also raised a Polish and Soviet flag on the Brandenburg Gate.

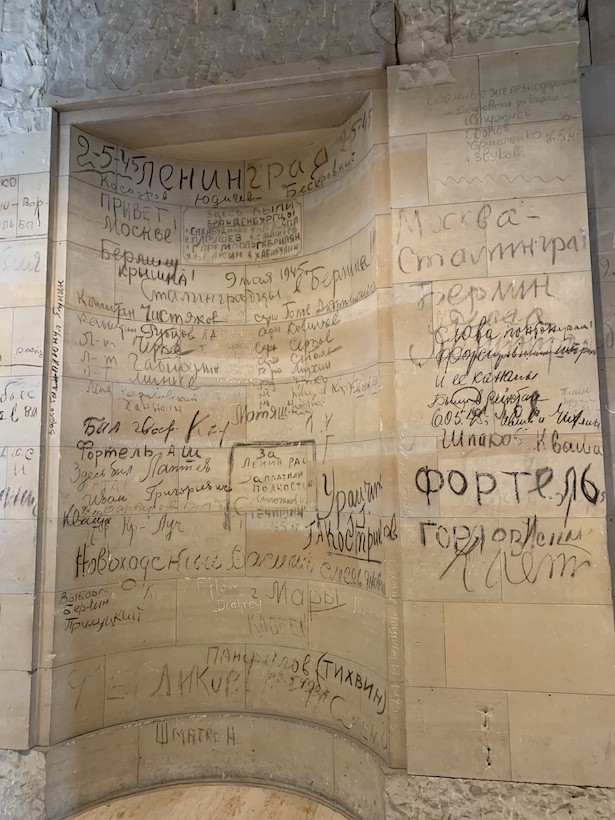

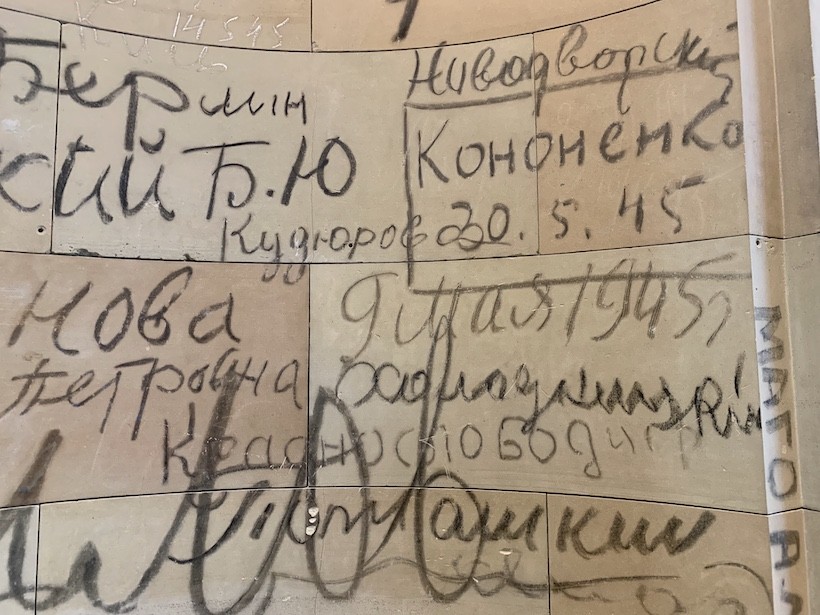

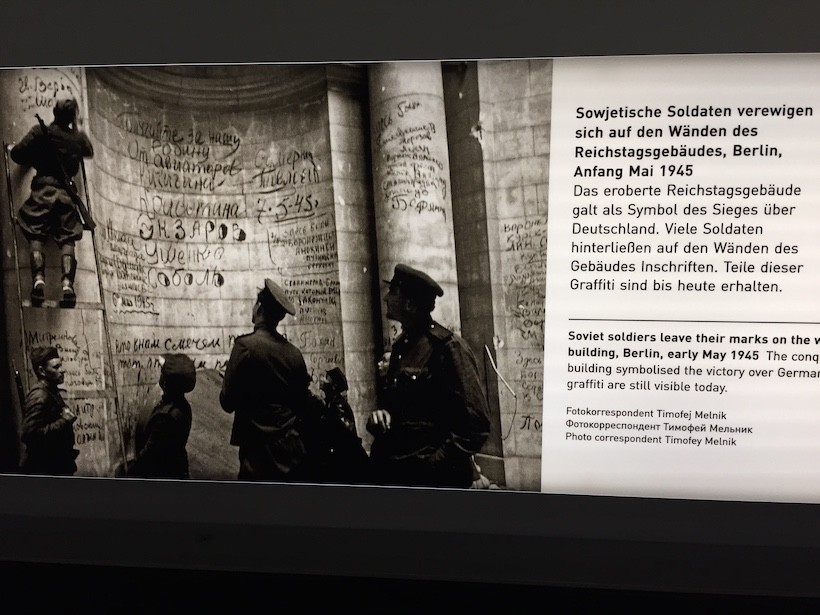

Graffiti left behind in Cyrillic by Soviet soldiers is still visible today on the walls of the Reichstag as a testament to the Russians’ liberation of the building and the city as a whole.

The back of the Reichstag, where the red flag was raised

Soviet soldiers left their mark on the walls of the Reichstag, German-Russian Museum

Soviet flag on the Reichstag, May 2, 1945

Surrender: House at Schulenburgring

Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide in their bunker on April 30, with Goebbels taking his own life a day later. Hitler’s successor as head of state and the only representative of the German Reich left living, Karl Dönitz, sought to negotiate with the British and Americans to avoid brutal reprisals from the Soviets, but unconditional surrender was the only acceptable path for the Allies.

In early May in the living room of a certain Mrs. Anni Goebels (no relation to her notorious namesake) at Schulenburgring 2 (16), an important moment in world history took place. Soviet General Chuikov had housed his headquarters in Anni’s ground floor apartment and, on May 2, German General Weidling, the last commander of Berlin’s defence troops, signed the surrender on Anni’s living room table.

The house at No. 2 is still standing, a plaque on its wall the only reminder to this momentous occasion.

Unconditional surrender: German-Russian Museum

A couple of days after the surrender of Berlin, German Field Marshall Keitel signed the unconditional surrender of all German forces, marking the end to the Second World War in Europe.

The signing took place in the officers’ mess of a German army school in Karlshorst in east Berlin on the night of May 8, 1945. Today the building is home to the German-Russian Museum (17) with a permanent exhibition exploring the war from both the German and Russian perspectives.

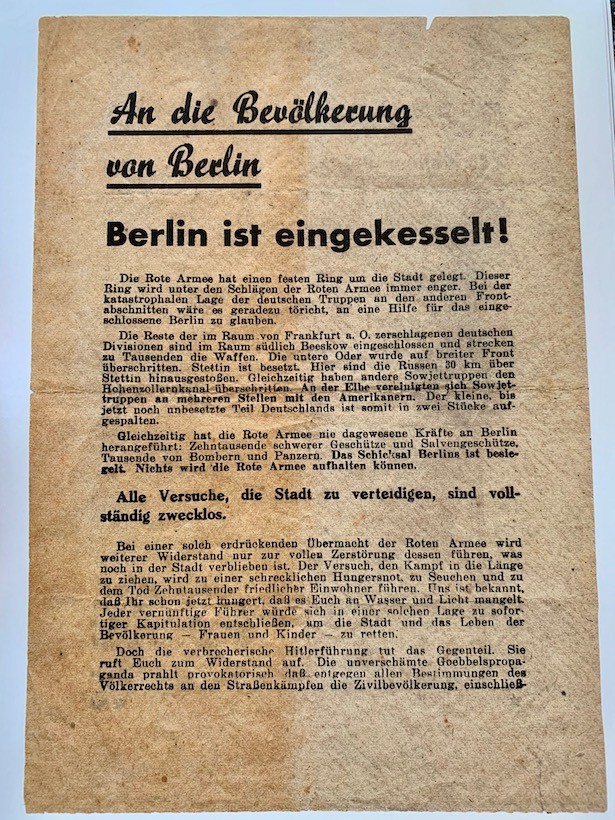

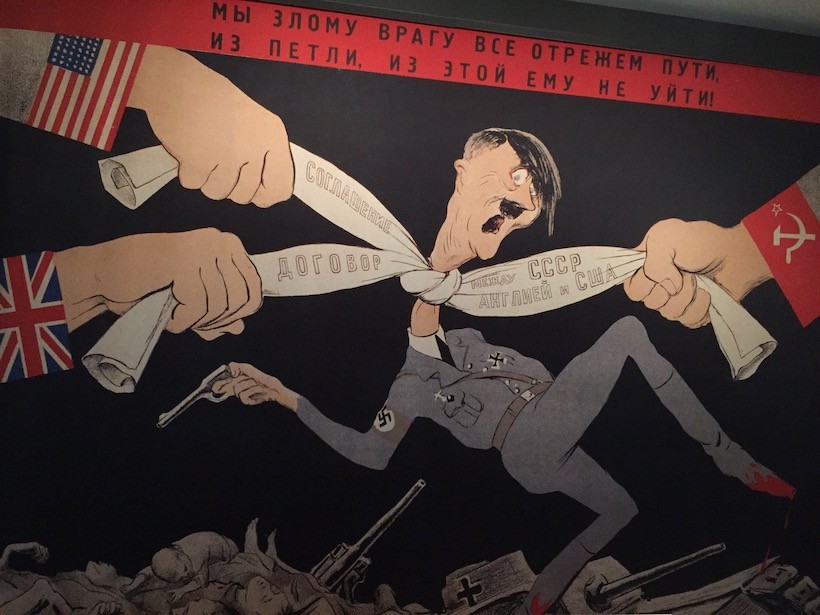

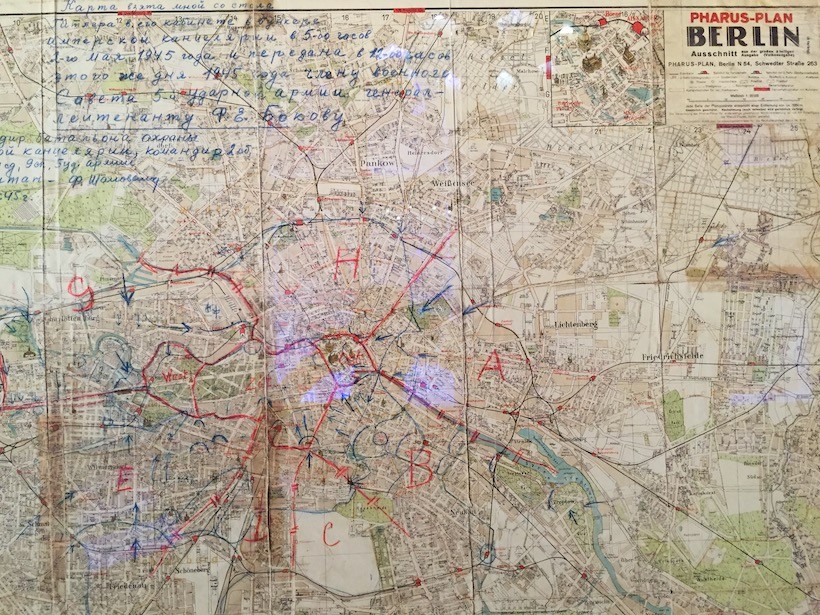

Besides the room in which the surrender took place, the museum has several other interesting items on display, including the table on which the surrender of Berlin was signed, a Red Army flyer calling for citizens to surrender with ‘Berlin ist eingekesselt’ (‘Berlin is encircled’) written on it, and an original map of Berlin found on Hitler’s desk in his bunker.

German-Russian Museum

Assault on the Reichstag

Soviet propaganda

Defence strategy, found on Hitler’s desk

The room where the surrender of Germany took place, with a film of the surrender on loop

Memorials and graveyards

During the Battle of Berlin, Soviet soldiers killed in action were mostly buried nearby. After the war, three larger memorials and cemeteries were built to commemorate the approximately 80,000 fallen Russian soldiers killed during the fighting.

Perhaps the most visited is the site in Tiergarten (18), which is the smallest of the three memorials but thanks to its location near the Bundestag and Brandenburg Gate is the easiest to get to. The two T-34 tanks on either side of the complex are said to be the first to have reached Berlin.

The Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park (19) is the largest war memorial in Germany and serves as a grave for 7,000 soldiers. The imposing statue on top of the mausoleum shows a victorious soldier standing on a crushed swastika, carrying a rescued German child. At the entrance to the grounds, another statue of a grieving Russian mother sits at the start of a lane of weeping willows.

The cemetery at Schönholzer Heide (20) is the largest Soviet cemetery in Berlin with 13,200 fallen soldiers buried there. It’s also the largest Russian cemetery in Europe outside Russia, and people still flock here to pay tribute. You can often find flowers, candles, and as we discovered, even one or two soldiers’ pictures.

Schönholzer Heide

Schönholzer Heide

Picture of a fallen soldier; Schönholzer Heide

Invalids’ Cemetery

Memorial to Polish soldiers, Volkspark Friedrichshain

Memorial to Polish soldiers, Volkspark Friedrichshain

What’s left of Hitler’s bunker?

The centre of power in Hitler’s Germany was the New Reich Chancellery, an enormous building 421 metres in length with endless hallways and enormous rooms designed to intimidate visitors. Destroyed during the Battle of Berlin, its ruins were levelled by the Soviets after the war. The Führerbunker (14), which was built underneath and was where Hitler committed suicide, was never fully demolished. Indeed, some of its corridors still exist but are sealed off to the public.

Some sources even claimed that the marble walls of the New Reich Chancellery were used in the building of the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park (19) as well as in the renovation of the nearby Mohrenstraße U-Bahn station (21). In a heavily destroyed city, with a lack of building materials and where quick solutions were needed, this doesn’t seem all that farfetched — although the claims have later been cast into doubt.

If you want to see what remains of Hitler’s final stronghold as well as a scale model of Germania used for the movie The Downfall, visit the Mythos Germania exhibition in Gesundbrunnen U-Bahn station.

Soviet War Memorial, Treptower Park

Is this all that’s left?

‘Mythos Germania’ exhibition

The last remaining facade at Voßstraße

Mohrenstraße underground station

The clean up: from rubble hills to rubble women

At the end of the war, Berlin lay in ruins. To clear the streets from rubble and start the slow process of rebuilding the city, the occupying forces put the local population to work. Interestingly, this is how many of Berlin’s hills came into being: giant mounds of rubble covered in turf.

In Volkspark Friedrichshain (4) alone, 2.1 million cubic metres of rubble were piled up into two mountains of debris — the remains of houses from the Mitte, Friedrichshain and Prenzlauer Berg districts of Berlin.

Teufelsberg (22), a man-made hill in the Grunewald area of Berlin, was created in the 20 years following the war by moving 75 million cubic metres of debris from the city. Included among the many buildings buried there is an unfinished Nazi military college designed by Nazi architect Albert Speer.

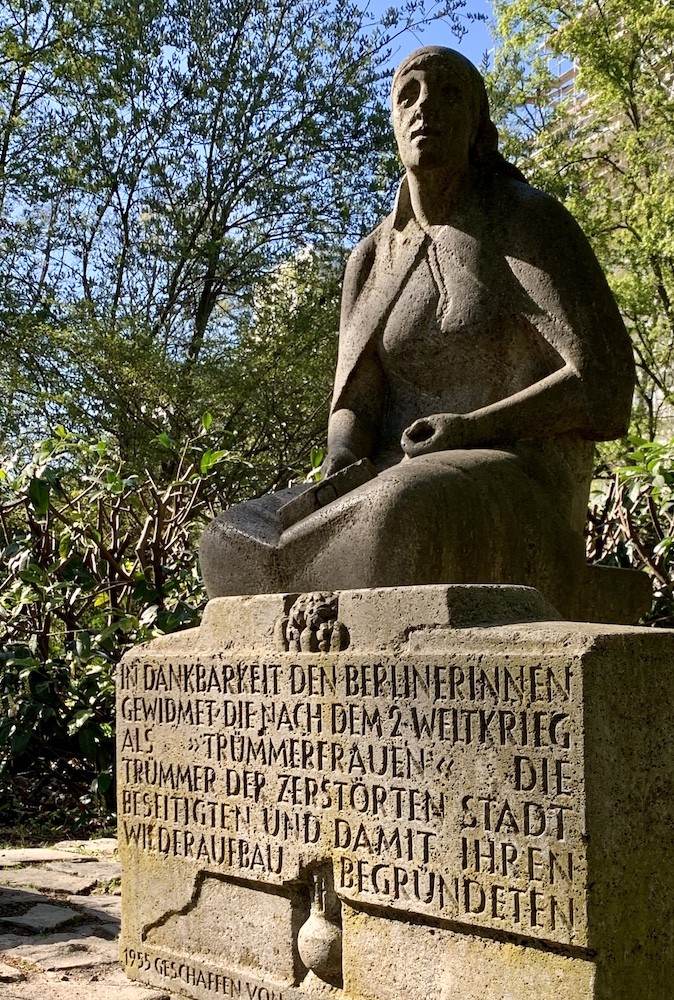

With much of the male workforce deceased or prisoners of war, the hard work of clearing the cities of rubble and reconstructing them fell largely to women. These women soon became known as Trümmerfrauen, or rubble women, and a number of memorials pay tribute to them, such as the one at the Rotes Rathaus (23) and near Rixdorfer Höhe in Neukölln (24).

These two dozen places serve as silent witnesses to the worst conflict that Berlin, Germany and the rest of the world has ever seen. A war that started from Berlin, was controlled from here and cost the lives of over 60 million people. These silent witnesses should remind us all of the consequences of inhumane, nationalist policies. And of the importance of democracy, freedom, cooperation and peace. The cornerstone of today’s Europe.